Wellbeing measures and data

This section provides an overview of the different approaches to wellbeing measurement. It helps you think through some of the key issues when designing a before-and-after survey and gives you a sense of what you can and can’t say with the data you’ve collected.

Types of wellbeing measure

Wellbeing can be measured using both subjective and objective measures. Using both types of measure can help you build a more accurate overall picture of your wellbeing outcomes and of what’s really important to how people feel and function.

What does a good wellbeing measure look like?

- Good quality: captures the concept of wellbeing (validity); gives results that can be reproduced (reliability) and picks up change (sensitivity)

- Easy to use: Succinct and suitable for use in surveys; easy to understand, score and interpret; provides helpful results.

Objective measures

These examine the observable factors that affect someone’s life, for example, whether they have a job or whether they have stable housing. Objective indicators attempt to measure a person’s quality of life using measures of education, employment, health, housing, income and environmental quality, among other factors that affect how they feel and function. You can read more about this in the section What is wellbeing? in this guide.

You’re probably already collecting data on objective measures. What you collect depends on what you want to achieve. For example, if you:

- work with adults in vulnerable housing situations, you might be measuring the number of people who secure stable housing

- want to improve people’s skills to help them get a job, you might be measuring how many people find work through your services

- run an English for Speakers of Other Languages class: you might measure how many people get a language qualification.

Objective measures are useful, but because they look at someone’s life from the outside, they only tell you part of the story. If you want to measure overall wellbeing, you need to ask them directly how they feel about their lives – their subjective wellbeing.

In this guide we will focus on the subjective measurement of wellbeing.

Subjective measures

These ask people directly how they’re doing. Individuals themselves decide what makes a difference to them about:

- how they feel day-to-day and overall

- how they function

- whether they feel their needs are being met.

Subjective wellbeing is referred to as ‘personal wellbeing’ by the Office for National Statistics and is measured using questions that provide a general impression of how someone is feeling. These are sometimes known as global measures.

These measures look at:

- an overall assessment of someone’s life, usually to find out whether they feel generally satisfied or not (sometimes referred to as evaluative wellbeing)

- their overall sense of purpose, and how well they function (sometimes referred to as eudaimonia)

- the positive or negative feelings they’ve had recently – for example, how happy or anxious they’ve been (also referred to as positive affect and negative affect).

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) measures subjective wellbeing across the UK, to assess these aspects of overall wellbeing.

ONS4 – the national measures for subjective wellbeing in the UK

Next I would like to ask you four questions about your feelings on aspects of your life. There are no right or wrong answers. For each of these questions I’d like you to give an answer on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is ‘not at all’ and 10 is ‘completely’.

| Measure | Question |

|---|---|

Life satisfaction | Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays? |

| Worthwhile | Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things that you do in your life are worthwhile? |

| Happiness | Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday? |

| Anxiety | On a scale where 0 is ‘not at all anxious’ and 10 is ‘completely anxious’, how anxious did you feel yesterday overall? |

Source: ONS. Personal well-being frequently asked questions

Using the Wellbeing Measures Bank

Using the Wellbeing Measures Bank

These and other global measures of wellbeing are included in the Wellbeing Measures Bank in this guide.

Domain-specific measures

Objective and subjective measures can be domain-specific – they can relate to those aspects of life that are most likely to be impacted by a project or programme or to be barriers or enablers of overall wellbeing.

Some examples of domain-specific subjective measures are:

- how lonely a person feels

- how satisfied they are with their job

- how optimistic they are about the future

You may want to use some of these measures to understand how and why wellbeing changes as a result of your activity, and to improve your Theory of Change. For more on Theories of Change, you can read the section on Planning your wellbeing evaluation in this guide.

Time-specific measures

Wellbeing measures can also be split by the timescale they aim to represent. Measures such as the ONS4 are included in longer-term panel data surveys and capture ongoing differences in wellbeing. These help us see trends and changes in wellbeing over longer periods of time.

Other measures are more short-term and use ‘in-the-moment’ data, such as the ‘mappiness’ application, which records wellbeing scores via a mobile phone. These are useful for linking emotions to very specific conditions, such as whether someone feels better after exercise, or how commuting affects their mood.

Other information you should collect

Demographic and socio-economic data

Collecting demographic and socio-economic data from your participants – such as gender, ethnicity and self-reported health – will help you build a more accurate picture of their wellbeing. By using questions such as these you can capture the variations in wellbeing among participants of similar groups or backgrounds. You can do this:

- At the start of your project – to look at whether there is existing Wellbeing inequality within your sample

- When estimating impact and the end of your project – by controlling for certain characteristics to help you better understand the impact of your project or programme. You can read more about this in the section on Analysing and interpreting your results in this guide.

Data on the role of other organisations or activities

If you’re looking to doContribution analysis, you’ll want to know what else is going on in someone’s life, including any actions of individuals or organisations that may be affecting an individual’s wellbeing. You’ll want to ask beneficiaries which other activities and services they are accessing and how frequently. This will help you estimate the role of factors other than your organisation in generating any wellbeing changes you may record.

Ethics in wellbeing evaluation

You should already be familiar with the general ethical considerations of evaluating your activities, and any wellbeing evaluation should fit with your established approaches and safeguarding policies.

Yet, there are some aspects of wellbeing evaluation which may require additional thinking to make sure your approach is ethical and sensitive.

The most obvious consideration is in the nature of subjective wellbeing questions themselves. Asking someone very personal questions about their lives – such as whether they feel happy, or lonely, or whether what they do in life is worthwhile – is very different from asking them how often they visit a museum, or go to the gym.

The research shows that most people think studying wellbeing is important, but some people may feel uncomfortable or distressed by the questions in your survey.

- You should make sure people know why you are asking these questions, and how important it is to understand their wellbeing in the context of your work with them.

- It should be clear that there is no ‘wrong answer’ and that people’s answers will not affect their access to your activities.

- If the questionnaire is administered by a member of staff or volunteer, prepare them for different reactions from people. You can use role play to test out the questions in a training session. Support the staff and volunteers by making sure they can report any problems or worries to you during the data collection stage.

- If you are working with vulnerable people, make sure you have a plan for supporting them during the survey and after they complete it. For example, they may disclose something that you need to follow up afterwards, or you may want to signpost them to other support services.

- You should report the findings back to people after you’ve analysed them and make sure they understand how you will use the results.

Here’s a practical guide from Oxfam for thinking about ethical issues in your evaluation.

The before and after survey

One of the main ways you’ll be collecting wellbeing data is through a survey, which will involve the development of a questionnaire and the collection and analysis of responses.

One of the main ways you’ll be collecting wellbeing data is through a survey, which will involve the development of a questionnaire and the collection and analysis of responses.

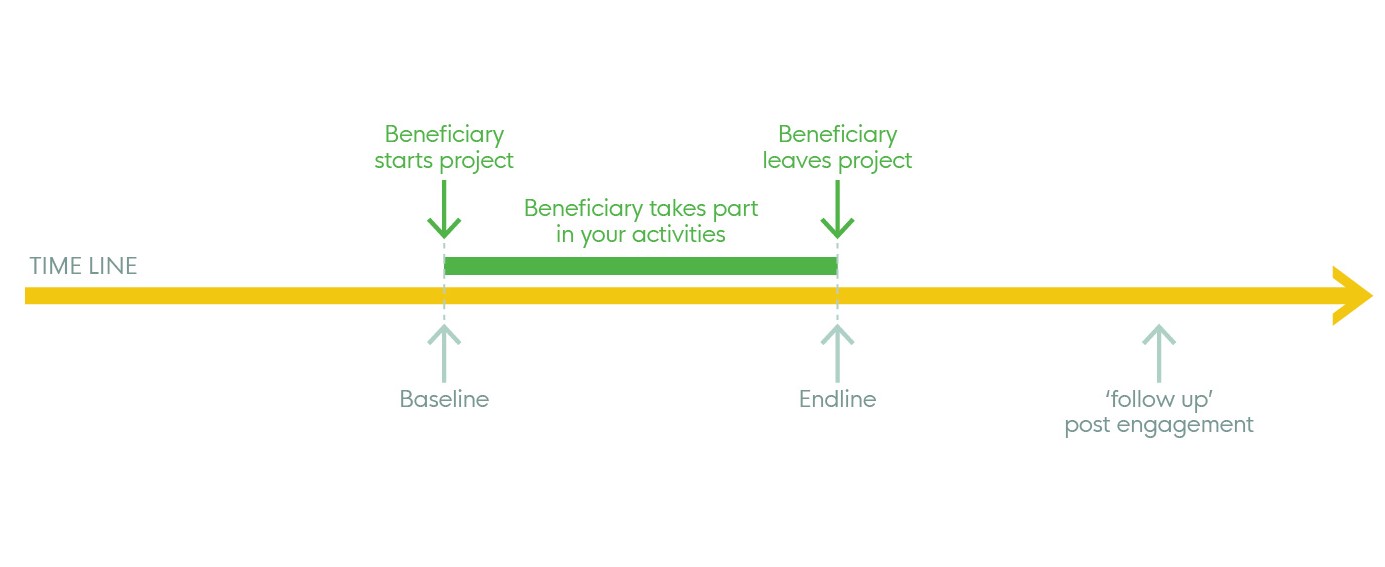

In abefore and After comparative survey, you will ask your participants to complete the same questionnaire at baseline – at or very near the beginning of their participation in your project or programme – and at endline – after your project has ended. This will allow you to measure changes in wellbeing at the end of your project, compared to your beneficiaries’ starting point.

You can also follow up with the same questionnaire three, six or 12 months after the end of your project or programme. Conducting follow-up questionnaires will help you estimate how long changes in wellbeing last. For example, if you record wellbeing improvements among beneficiaries 12 months after your programme has ended, you can claim that programme’s effects last for at least 12 months.

In order to estimate or establish whether your organisation is responsible for any changes in wellbeing, you will still have to think about contribution or attribution. Read more about this in the section on Analysing and interpreting your results in this guide.

There may be cases where you are delivering a project that doesn’t have a clear start and end date, for example, a drop-in service. You should still consider asking your beneficiaries to complete a questionnaire when they first access your service or project and then again after a certain number of appointments or sessions. This number will depend on your Theory of Change and when (after how many months) you expect wellbeing to improve.

Designing your survey

- Start your survey with a clear introduction, in which you tell respondents what data you are collecting and why, as well as how long the survey will take to complete. Make sure your questionnaire includes clear guidance on how to complete questions.

- Only include the measures that are necessary to answer your evaluation questions. This will help keep the length of the survey manageable and make the best use of your and your respondents’ time.

- Use standardised or validated wellbeing questions such as those found in our Wellbeing Measures Bank. Most of the wellbeing questions you’ll be using will be scaled: they’ll require respondents to select one option from a scale. Avoid changing the wording of the questions or the order of the scale if you want to compare your findings to other data.

- Ask wellbeing questions as early on as you can. People’s answers will be influenced by questions from earlier in the survey, so try and ask wellbeing questions right at the start. Ask demographic and other profile questions at the end of the survey.

- Make sure your survey complies with GDPR legislation. It is important that nobody can identify the people who took part in your survey from your results. So you need to handle everyone’s personal information in line with the Data Protection Act 2018 and GDPR (EU General Data Protection Regulation) 2018. You should include your GDPR statement at the top of your survey and secure consent from your respondents through a tick-box or similar. For more information, visit the NCVO Knowhow section on data protection.

It is important that:

- people completing surveys understand how that data will be used and provide explicit consent for that

- data collected about individuals is held securely

- in presenting results, individuals cannot be identified.

Survey format

Think about your audience and choose the best format for them. You can collect data using:

- a paper questionnaire

- an online questionnaire

- a phone survey.

The option you choose will depend on the literacy of your respondents, their access to the internet, the expertise of staff asking questions and your budget. If you’re doing a face-to-face survey, it’s important to pick the right person to ask the questions. They need to:

- be capable and comfortable asking the questions – avoid asking questions in a group setting and make sure the interviewer is impartial;

- understand why you’re asking the questions and how you will use the answers;

- be able to support and reassure people if the questions are upsetting and be able to handle negative responses to potentially difficult questions about emotions.

For more guidance on using questionnaires in evaluation, see NCVO Knowhow.

Survey checklist

Below are a few things to check before you start collecting data. Ensure you:

- Test your survey before using it. Ask a colleague or someone who hasn’t designed it to give you feedback on the length and number of questions.

- Take cultural and language differences into account. Some people may need help with some words, for example, if English isn’t their first language or if some words mean different things to them. The term ‘optimistic’ can be interpreted differently across different cultures, for instance. Translating questions into other languages could change their meaning, so tread carefully. Some measures such as the ONS4 and S/WEMWBS have been translated.

- When you repeat your survey, remember to measure the difference in wellbeing between the start and end of your programme and do your survey in exactly the same way before and after – right down to the order of the questions.

In this section you learned:

- How wellbeing is measured and what the data can tell us

- The key issues to consider when designing a before-and-after survey

- How to carry out an evaluation ethically.

You’re ready to learn how to choose the best measures for your evaluation!