Planning your evaluation

This section will prepare you for wellbeing measurement, including:

- the development of your theory of change,

- choosing an evaluation design,

- data collection

- and reporting results.

Phases of an evaluation

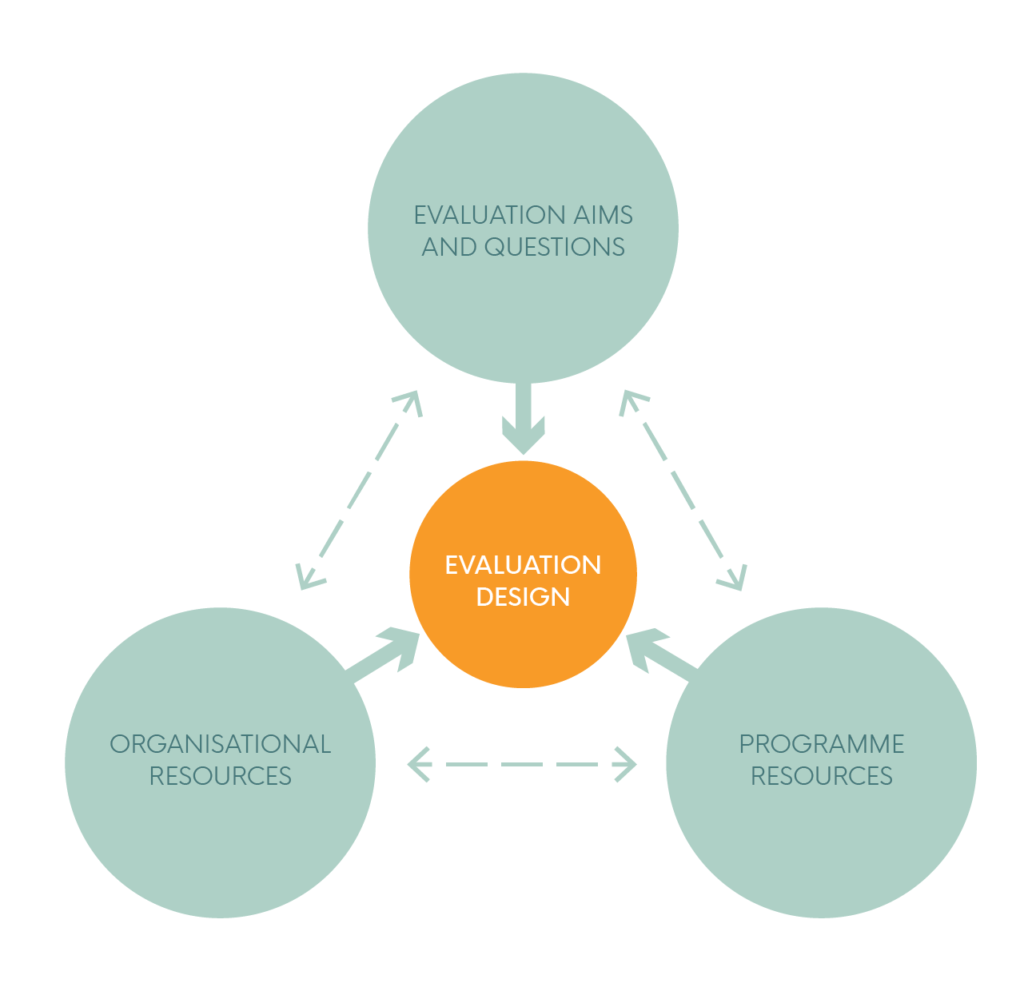

Your evaluation design will be shaped by what you are trying to find out, who your audience is, and what action you will take with your findings. You will develop your approach to be appropriate to your project or programme, the context of the activities, and your resources – including funding, expertise and other constraints.

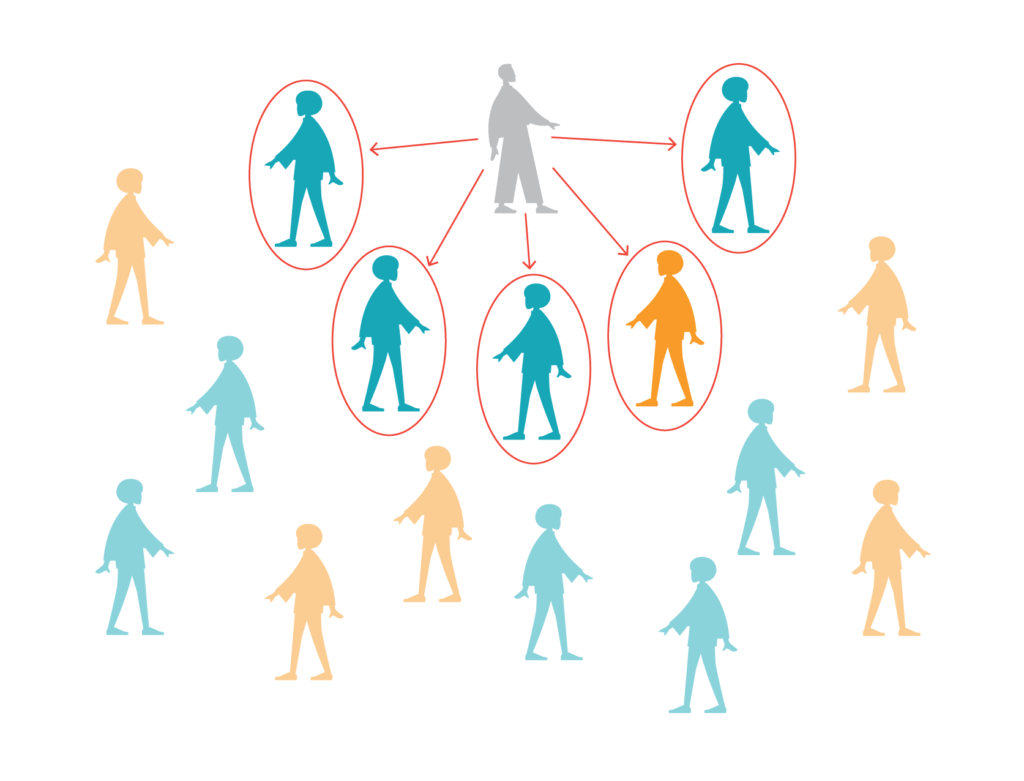

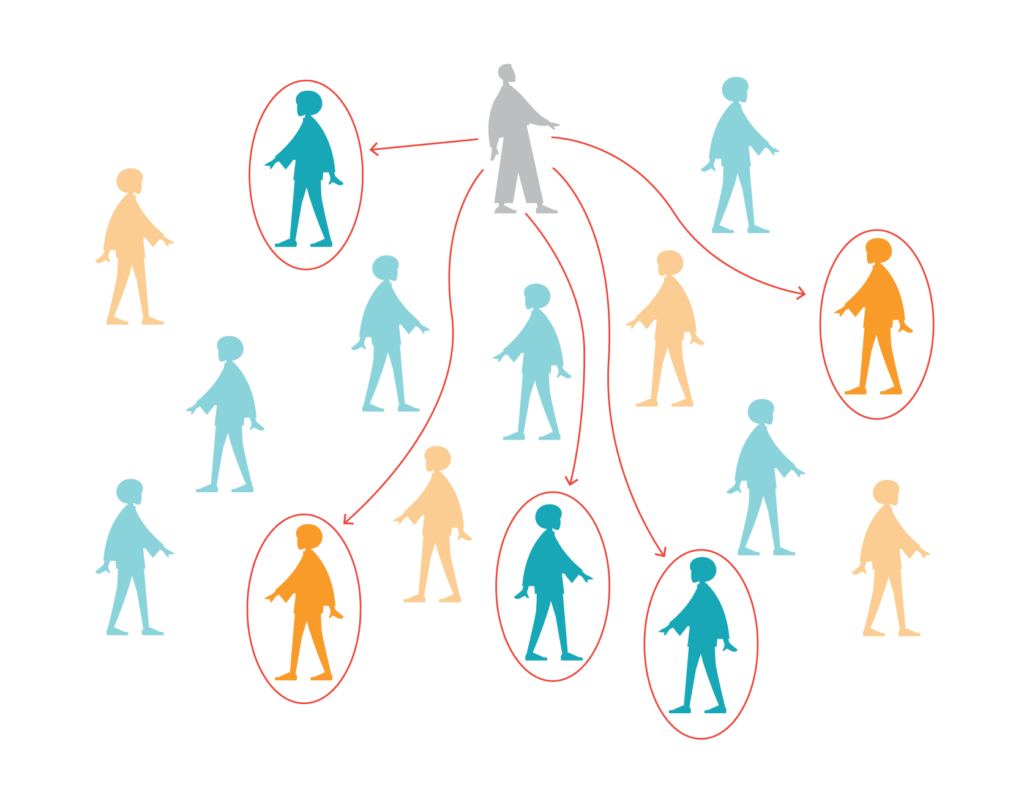

Including multiple perspectives

Including multiple perspectives

When planning your evaluation, you should include the views of stakeholders and consider the perspectives of the individuals and groups you are accountable to.

Developing a Theory of Change

Once you have identified the project or programme you would like to evaluate, you should make use of existing wellbeing evidence, your own knowledge of your project and any data you have gathered about the potential effects of your activities to develop a Theory of Change.

What is a Theory of Change?

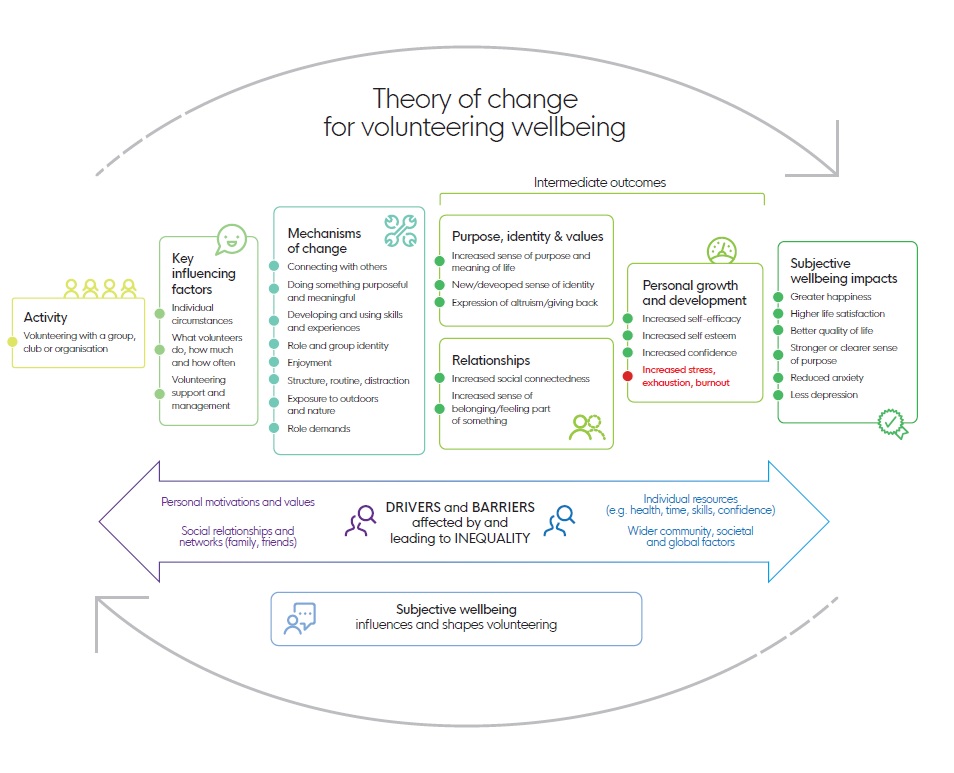

A Theory of Change describes how your activities lead to outcomes through logical pathways, drawing out ‘how’ and ‘why’ you expect change to happen. Typically, it takes the form of a diagram that presents an outcomes chain, starting with inputs (the resources that go into your project or programme), followed by activities and outputs (the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ of your intervention) that lead to wellbeing outcomes and impact.

Crucially, a Theory of Change tests each step in the process to ask ‘how and why does this step lead to the next?’

Here’s an example of an evidence-based Theory of Change that shows how taking part in volunteering can impact the wellbeing of volunteers:

How can a Theory of Change help?

Your Theory of Change will help you explain the ways in which your activities may impact your wellbeing, show the value of your work and help you identify meaningful outcome measures.

Wellbeing can be represented in one of two ways: as an intermediate outcome that leads to a different final outcome, such as sustained employment, or as the final outcome or impact of a project itself, for example, where better housing conditions lead to improved wellbeing.

Your Theory of Change should include positive as well as any negative changes to beneficiaries. It will also present barriers, enablers and mechanisms of change – the context that helps make your project or programme successful or creates barriers.

You can find more guidance on developing a Theory of Change on the NPC resources page

The Happy Museum Story of Change resources can help you develop your Theories of Change through workshops and conversations with stakeholders.

![]() Covid-19: things to consider

Covid-19: things to consider

You may want to account for some of the effects of the pandemic in your theory of change. The psychological and social effects of Covid-19 may cause the wellbeing of your beneficiaries to worsen (or fail to improve), despite your activities.

Choosing your evaluation approach and methods

Your evaluation design will inform the methodology you use to answer your wellbeing evaluation question/s. The choices you make will shape how you collect and analyse wellbeing data.

Below you’ll find descriptions of the main types of wellbeing evaluation, with appropriate methodologies and methods you can use.

Outcomes evaluation

Did your project or programme improve wellbeing as planned in the short, medium and longer term and for whom?

This is about measuring and evaluating the wellbeing changes that may have occurred for the individuals, groups and communities you work with. Your Theory of Change will help you establish whether you are expecting wellbeing to change in the short, medium and/or longer term. If your evaluation budget allows for it and you have an adequate sample size, and experienced evaluator, you may also want to:

- consider contribution or attribution – the extent to which your organisation is responsible for the changes

- look more closely at differences in wellbeing scores between the different groups that you work with, to highlight wellbeing inequality.

There is more on both these issues in the section on Gathering qualitative data in this guide

There are two main types of evaluation questions you can ask, and the design you choose will determine the quality and strength of your findings.

1. Has the wellbeing of your beneficiaries changed during or following their participation in your project or programme?

Typically, you will be:

- Measuring shorter-term changes in the wellbeing of your beneficiaries, including changes to their material circumstances, awareness, attitudes, knowledge and skills.

- Using a Before and After comparative survey to gather data from your participants.

- Reporting percentage or mean wellbeing scores for your wellbeing outcomes for your beneficiaries at baseline (taken at the beginning of your project) and comparing it to their endline score (taken at the end of your project).

You may also be doing the following.

- Measuring or exploring change using qualitative methods as part of a Mixed-method design in which you use qualitative data (such as stories and opinions) alongside a survey. There is more on this in the section on Using qualitative data in this guide.

- Estimating your organisation’s contribution to this change, or benchmarking your progress against national or regional data or a previous project. There is more on addressing causal questions in the section on Analysing and interpreting you results in this guide.

Impact evaluation

2. What was the impact of your project or programme on wellbeing, and were you responsible for change?

Typically, you will be:

- Measuring the medium- to longer-term changes in the wellbeing of your beneficiaries, including changes to their material circumstances, awareness, attitudes, knowledge, skills and/or behaviour. This would likely include measuring the wellbeing of your beneficiaries at several points in time, including at baseline, midline, endline and with a six-month to one-year follow-up. Any follow-up measurement would help you estimate how long your wellbeing improvements last.

Using a control group in an Experimental design or Quasi-experimental Design as a comparator. This would help you understand the extent to which your project or programme had caused the impact.

- Reporting mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for your wellbeing outcome variables and conducting statistical tests, such as t-tests to compare the mean scores of your beneficiaries at the beginning and end of the programme. If you’re using a control group, you may also be reporting on the impact sizes – the difference between the means of your control group and treatment group – to help you understand the magnitude of your impact. Read more about this in the section on Analysing and interpreting you results in this guide.

The What Works approach

The What Works approach

As a What Works Centre, we adopt the principle that good decision-making should be informed by high quality evidence. We believe in the “Test, Learn, Adapt” approach to developing public policy – an experimental approach that uses Randomised Control Trial (RCT) to decide that works and what doesn’t.

How and why did the activity make a difference to wellbeing?

An outcomes or impact evaluation on its own may not be sufficient to build a detailed understanding of why and how an intervention worked. You may want to explore the causal assumptions behind the successful or unsuccessful implementation of a project and examine the mechanisms that enable it to work in specific contexts and populations.

Whether you’re using a qualitative method – such as focus groups – within a Mixed-method design or using a qualitative methodology on its own – such as Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) or Realist evaluation – you will be:

- Exploring the processes, mechanisms and/or contextual factors that make your project or programme successful. This would help you build an understanding of what’s needed to make your project or programme work elsewhere.

- Gathering qualitative data from focus groups or in-depth interviews to confirm or verify the causal mechanisms of change outlined in your Theory of Change and explain how your project or programme made a difference to wellbeing.

How efficiently did your project or programme achieve wellbeing outcomes?

Once you’ve established that your project or programme has led to improvements in wellbeing, you might also want to know what the resource implications or costs are of doing so. This will involve selecting an appropriate economic evaluation methodology to calculate a wellbeing cost-benefit ratio or measure the monetary value of wellbeing improvements. You can read a seven-step guide to estimate wellbeing cost effectiveness with less-than-perfect information.

Given the effects of the pandemic on the wellbeing of your beneficiaries you may find it difficult to measure the effects of your activities as the pandemic is likely to be the primary factor influencing your beneficiary group. This is a good time to explore developmental evaluation approaches which are better suited to measuring change quickly and as it emerges.

Data collection

Your evaluation question/s and methods will shape the tools you use for data collection. Most wellbeing evaluations will:

- involve a survey…

(You can find out more about this in the section on Wellbeing measures and data in this guide.) - …that uses wellbeing measures…

(Go to the section on Measuring wellbeing in this guide for more information.) - …possibly alongside the collection of qualitative data.

(Read more in the section on Gathering qualitative data for more on this.)

Well-chosen and implemented data collection methods are essential to address your evaluation question/s and to generate wellbeing data that can provide meaningful insights for your organisation, beneficiaries and wider stakeholders.

In a before-and-after evaluation design, you will need to start collecting data before your project or programme starts and should start planning for this before starting delivery. If you are not able to collect data at that point in time, you will need to use a retrospective survey to collect data.

It is likely that the pandemic has led you to shift to online delivery and that you will continue to deliver online or an alternative blended form for the coming months. Now is a good time to think about how you are delivering your activities and whether your new model is working. There are plenty of resources to help you think about how and what to evaluate online and in rapidly changing contexts.

In this section you learned:

- How to develop your theory of change and use it to guide your evaluation design,

- Different evaluation approaches and how to choose the one for you

- What to consider in data collection

- and how to report your results.

You’re ready to learn about wellbeing measures and data.

Or, keep reading for a deeper dive into addressing bias in your evaluation

Deeper dive: addressing bias

Below are some of the things you should think about when collecting your wellbeing data.

Sampling

As part of your evaluation, you will collect data from a sample of individuals and use it to draw conclusions about your larger population of interest. The way you build your sample will affect the quality of the wellbeing data you are able to collect.

On the whole, a more robust sampling method will make your results less biased and easier to generalise. Resources may not always allow you to adopt the most rigorous strategy, and the table below can help you decide between different basic sampling methods. You must be clear about what you can and can’t conclude from your results, and whatever strategy you choose, remember to:

- describe it in your evaluation report

- be transparent about the strength and quality of your findings.

Convenience sampling (non-probability sampling)

| What is it? | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| You will choose your participants based on how easily you can recruit them. They may be individuals who access your services regularly or people who volunteer to be part of your evaluation. | A quick and cheap way to build a sample. | your findings are likely to be biased. This is because your sample may be made up of individuals who do not accurately represent your beneficiaries. This is due to things such as self-selection bias - where individuals with higher wellbeing are more likely to participate. |

Purposive sampling (Non-probability sampling)

| What is it? | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| You will use your own judgement to select participants based on their specific characteristics. You might do this by setting quotas for specific demographic groups or by using a snowballing strategy to recruit hard-to-reach individuals and groups. | useful for exploring outcomes and impact among specific individuals or groups you may be interested in. | There are risks of researcher bias - as your evaluator will be choosing who makes up the sample; however, these can be minimised by being transparent about how you select individuals. You may find it takes time to recruit certain individuals, and knowing your target group well can help make recruitment more successful. |

Probability sampling

| What is it? | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| You will choose individuals from a population at random. You are only likely to use this method if you are evaluating a large-scale intervention and can build large samples of and have a list or easy access to the individuals who make up your population. | allows you to make statistical generalisations about your population with a high level of reliability and minimal bias. | This option is often costly and requires significant evaluation or research expertise. It is unlikely that you will be using an entirely random sampling method, and you can split your population into clusters (eg. by geography or age) to make the sampling more manageable. |

For more information on sampling, see BetterEvaluation

If you want support deciding which method to use, get in touch at evaluation@whatworkswellbeing.org.

If you want support deciding which method to use, get in touch at evaluation@whatworkswellbeing.org.

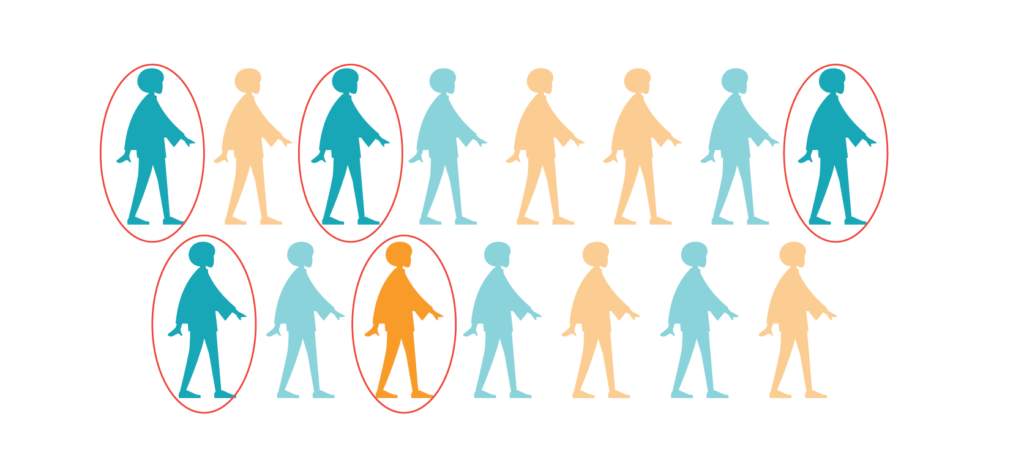

Drop-outs and attrition

You may find that your beneficiaries do not complete your programme or that those who do don’t engage in evaluation activities, such as surveys or interviews. This is known as your Attrition rate and can introduce bias in your results, as well as skewing your wellbeing data.

You should always try to be transparent about your drop-out rates and incomplete survey responses. You should try and reflect on which individuals drop out of your evaluation and why.

For more guidance on drop-out and attrition, see this video from MIT.